there were no problems found – there

were – but that is what testing is all about.

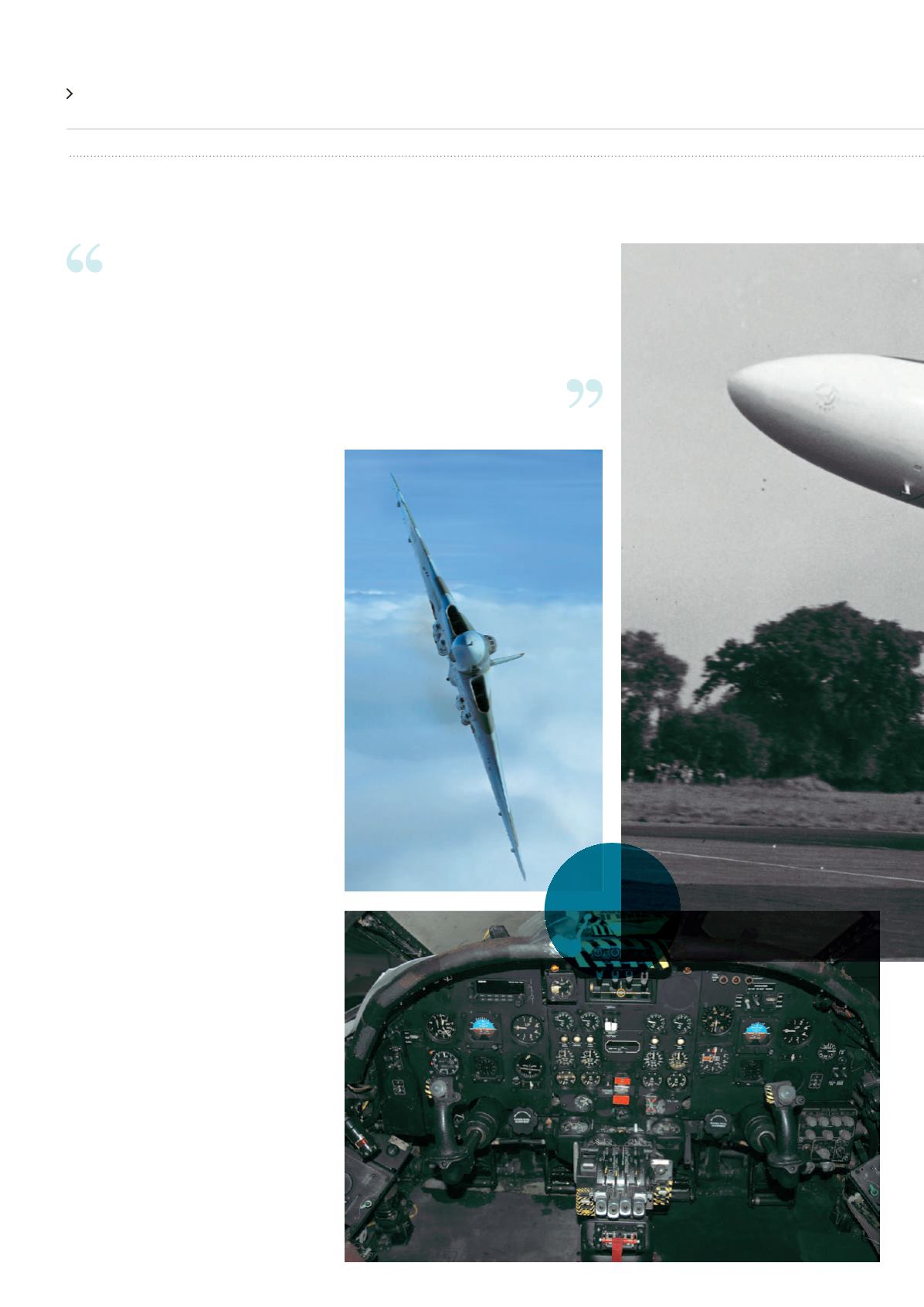

By October, XH558 was ready to move

again under her own power. Slow and fast

taxy tests followed, including deployment

of the brake parachute.

Finally, after 26 months, with over

100,000 man-hours and £7million spent,

Vulcan XH558 was ready to fly again.

Thursday 18 October 2007 was a perfect

day, and in front of the crowd of those

who had worked on the project, XH558

roared down the runway and soared

into the air. There were shouts, cheers

and tears of joy – so much effort by so

many people. I felt elated, but remember

thinking “I can’t relax until she’s back on

the ground”. After a 30-minute flight, our

test flight crew brought her back for a

perfect landing. We had done it. Safely.

The restoration of Vulcan XH558

has been hailed as the world’s most

challenging heritage aviation project

ever – the Everest of aircraft restoration. I

did wonder whether I was going to end up

as Mallory or Hillary….

Aircraft Operations

Following further test flights to resolve

problems with the avionics, XH558

was awarded her ‘Permit to Fly’ in July

2008. Two days later, she flew her first

display for an enthralled public at RAF

Waddington. Since then, XH558 has

flown more than 230 hours in front of

twelve million smiling and proud people

at events during over 160 flights around

the UK and Europe.

To keep the aircraft in top condition,

checks on the engines, landing gear and

critical structure are driven by flying

hour milestones. Every winter, the aircraft

undergoes a thorough inspection and

lubrication; critical components which

have a calendar life, such as the ejection

seats, are overhauled. This is not cheap: to

keep XH558 flying costs around £2million

per annum, for 40-50 flying hours.

Concordia

Merchant Taylors’ School

Every winter, the aircraft undergoes a

thorough inspection and lubrication; critical

components which have a calendar life, such

as the ejection seats, are overhauled